Tags

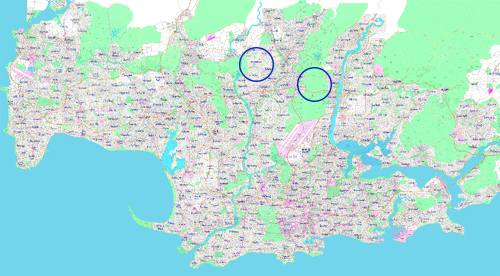

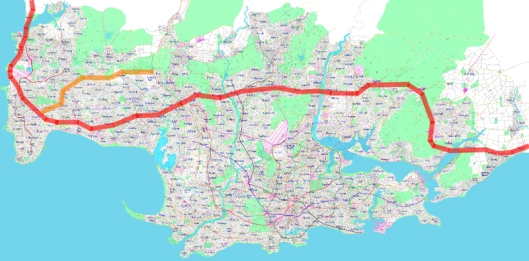

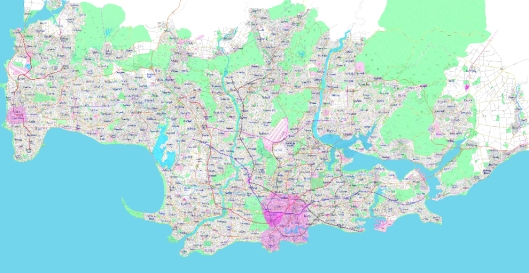

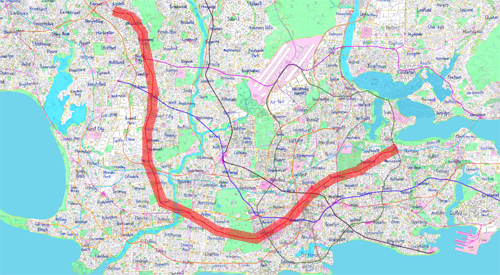

As I’m back posting on this blog, I thought I might as well continue working my way through detailing the city’s Metro system. Line 3, or the “Red Line”, is a really important route running in a general “U” shape east-west across the city. Let’s check it out generally: This line is perhaps more similar to “Line 1” than to “Line 2“, because it passes right through the central city and back out the other side. Once you think about it, there’s good reason to want a Metro line to do just that, as it means along the central section you’re picking up and dropping off a lot of passengers all the time – keeping the trains nice and full and busy in what was probably the most expensive part of the system to construct. With a line that terminates in the city centre, such as Line 2, it’s going to start losing passengers from its “peak load” level on the city fringe but won’t be as likely to be picking up passengers because they won’t have too many “destination” stations left on that line. So your central part of the line isn’t used as much as it might have been.

This line is perhaps more similar to “Line 1” than to “Line 2“, because it passes right through the central city and back out the other side. Once you think about it, there’s good reason to want a Metro line to do just that, as it means along the central section you’re picking up and dropping off a lot of passengers all the time – keeping the trains nice and full and busy in what was probably the most expensive part of the system to construct. With a line that terminates in the city centre, such as Line 2, it’s going to start losing passengers from its “peak load” level on the city fringe but won’t be as likely to be picking up passengers because they won’t have too many “destination” stations left on that line. So your central part of the line isn’t used as much as it might have been.

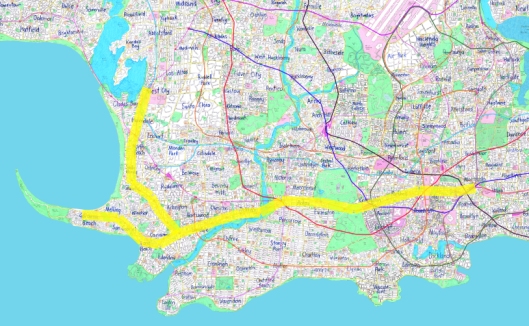

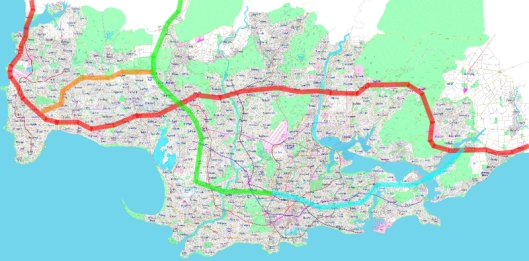

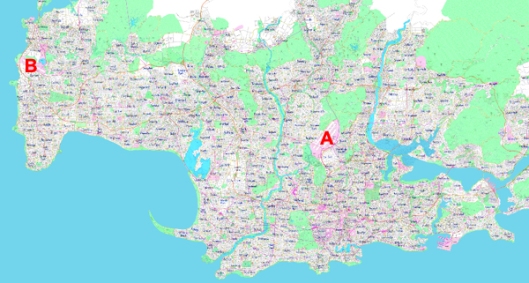

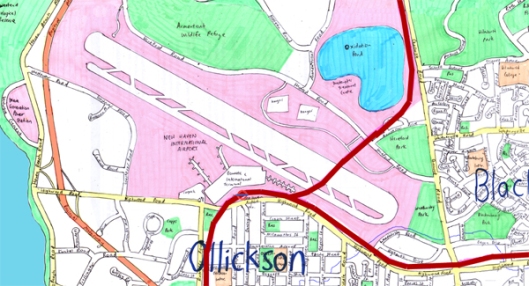

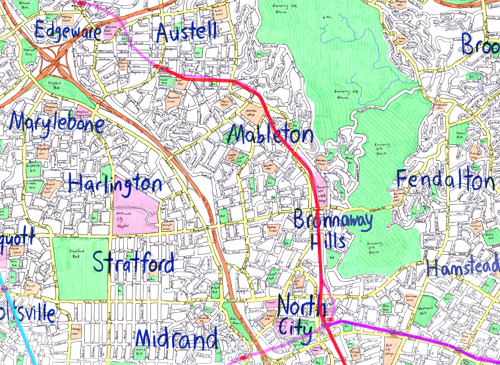

Starting in the northwest corner, let’s have a look in a bit more detail at what Line 3 is like. North City is a pretty major sub-regional centre, while areas north of it probably largely developed in the early part of the 20th century – to a reasonable density but probably mostly standalone houses with some terraced housing and perhaps some more recent low to medium rise buildings along the main roads. I’m guessing that it’s quite likely not all trains proceed past North City, with some likely to terminate or begin their runs there due to the lower demand further north. One thing that’s never quite felt right is where the line ends, perhaps that’s something I need to come back to in the future. Potentially I could pull the whole line back to North City with commuter rail handling further north (as otherwise we realistically need four-tracks with two for commuter trains and two for the metro trains, perhaps a bit unrealistic).

North City is a pretty major sub-regional centre, while areas north of it probably largely developed in the early part of the 20th century – to a reasonable density but probably mostly standalone houses with some terraced housing and perhaps some more recent low to medium rise buildings along the main roads. I’m guessing that it’s quite likely not all trains proceed past North City, with some likely to terminate or begin their runs there due to the lower demand further north. One thing that’s never quite felt right is where the line ends, perhaps that’s something I need to come back to in the future. Potentially I could pull the whole line back to North City with commuter rail handling further north (as otherwise we realistically need four-tracks with two for commuter trains and two for the metro trains, perhaps a bit unrealistic).

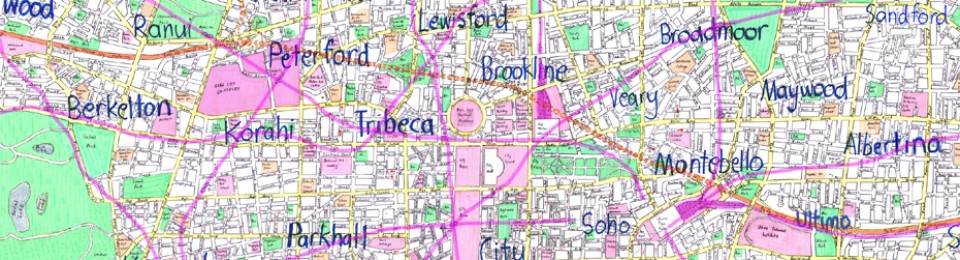

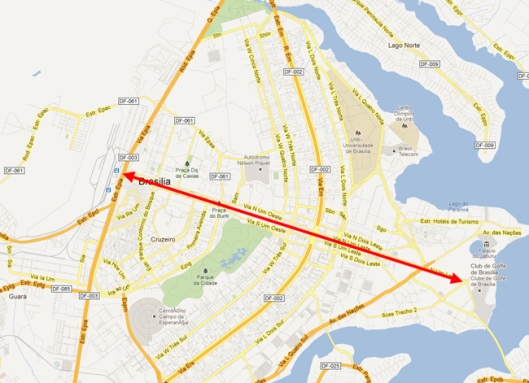

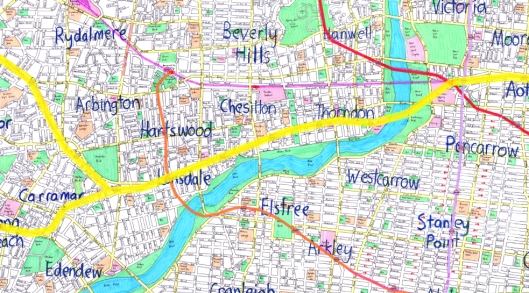

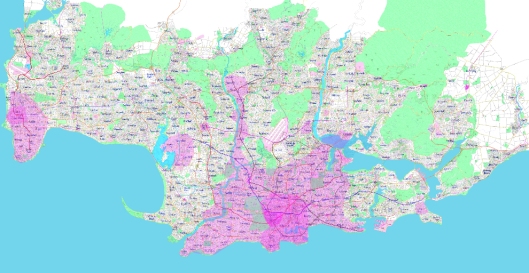

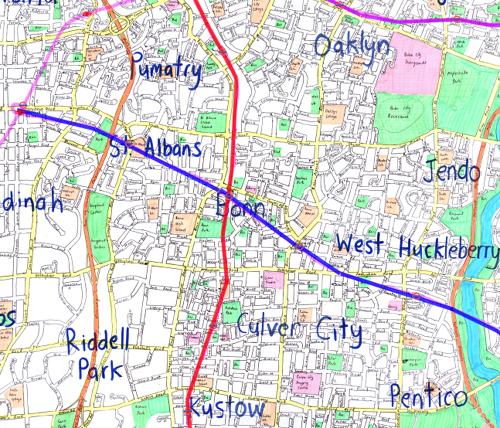

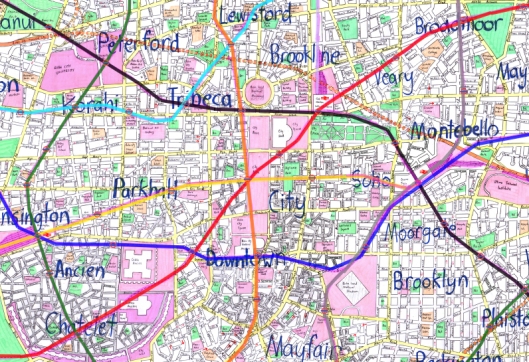

Shifting further south now, we come into the area the feels like the core patronage generator for this line – a series of pretty dense town centres focused around the metro line as well as some larger employment areas further to the west: Further south again is generally a similar story, with the inclusion of a really key interchange point with the Aqua Line (Line 5) probably used by a lot of people to transfer as Line 5 then serves a number of really important inner suburbs and cuts across the northern part of the city centre – also passing pretty close to the University.

Further south again is generally a similar story, with the inclusion of a really key interchange point with the Aqua Line (Line 5) probably used by a lot of people to transfer as Line 5 then serves a number of really important inner suburbs and cuts across the northern part of the city centre – also passing pretty close to the University.  From this point the line turns to the east and heads towards the central city. The large area with a gridded street network was probably built in the late 19th century and could be similar to large tracts of Brooklyn in New York City (so pretty intense).

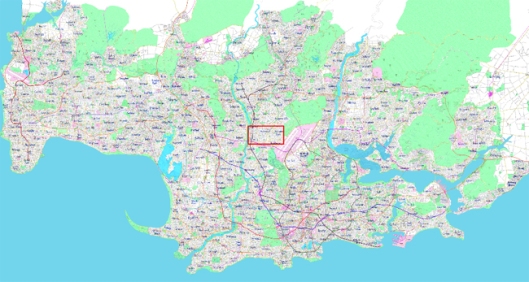

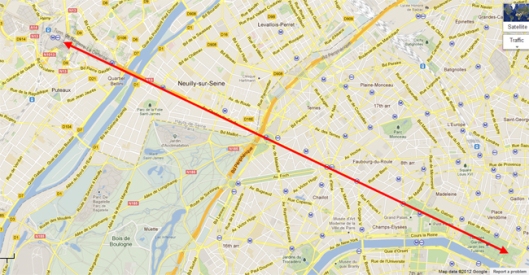

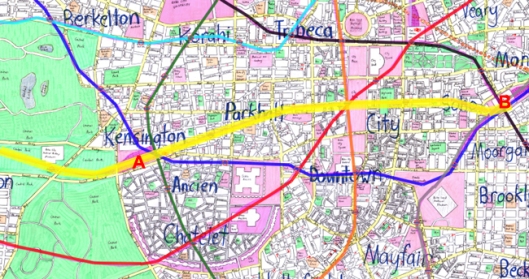

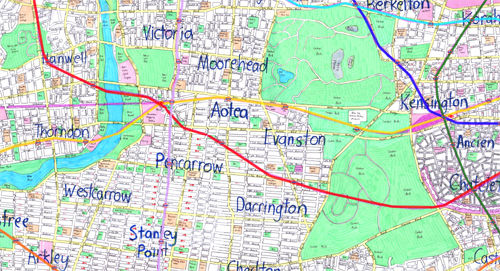

From this point the line turns to the east and heads towards the central city. The large area with a gridded street network was probably built in the late 19th century and could be similar to large tracts of Brooklyn in New York City (so pretty intense).  The line then passes underneath the very oldest part of the city – from the Middle Ages, as it once again turns northwards on its way through the city centre. In this section there are a huge number of interchange with other lines, the Civic Station commuter rail terminus and obviously the massive employment concentration that’s in the city centre. The line cuts southwest to northeast across the central city, probably carrying a large number of shorter trips on this section as people travel around the very inner city:

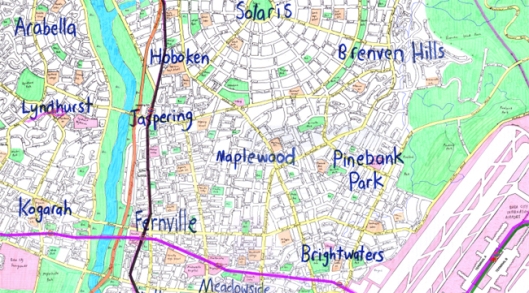

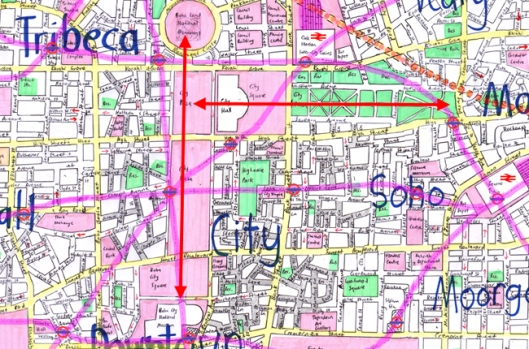

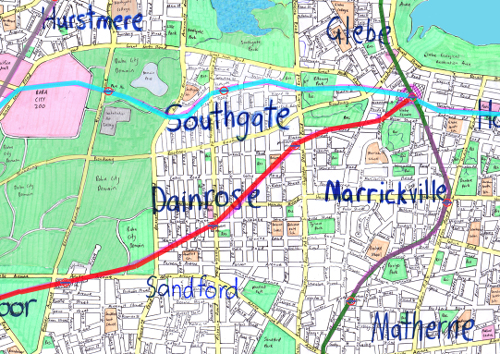

The line then passes underneath the very oldest part of the city – from the Middle Ages, as it once again turns northwards on its way through the city centre. In this section there are a huge number of interchange with other lines, the Civic Station commuter rail terminus and obviously the massive employment concentration that’s in the city centre. The line cuts southwest to northeast across the central city, probably carrying a large number of shorter trips on this section as people travel around the very inner city: From here it’s not too far to where the line terminates – at a fairly major interchange station at Glebe. This eastern section is probably reasonably busy right through it – due to transfers from Glebe, but clearly not as busy as the central and inner-western parts of the line. I think generally it balances out reasonably well though:

From here it’s not too far to where the line terminates – at a fairly major interchange station at Glebe. This eastern section is probably reasonably busy right through it – due to transfers from Glebe, but clearly not as busy as the central and inner-western parts of the line. I think generally it balances out reasonably well though: I think that perhaps after Line 1, this line could be one of the busiest on the network. I’m not entirely sure about whether it would have been one of the earlier or later lines built on the network, certainly not the earliest but at the same time it doesn’t feel like it would have been recently constructed – as there has clearly been a land-use response to it that has been happening for quite some time.

I think that perhaps after Line 1, this line could be one of the busiest on the network. I’m not entirely sure about whether it would have been one of the earlier or later lines built on the network, certainly not the earliest but at the same time it doesn’t feel like it would have been recently constructed – as there has clearly been a land-use response to it that has been happening for quite some time.